When Kay is restless, sleepless, between tasks, or when her spirits are low, she thinks of her ‘self’ as an agitated other who cannot be banished but must be temporarily quieted or forgotten. “I forget myself,” she says, “in archives.” Pretty much any random archive seems to serve her purpose, as long as it is easily accessible from the comfort of her desk, for example, online collections such as city maps, census records, photo archives, old newspapers.

The other day she missed a meeting with me. I didn’t mind. I knew she was subduing the agitated self by digging into something. And true to form, she turned up today carrying a small but shiny gem found in the now-digitized Hastings Banner, the local newspaper for Hastings, Michigan.

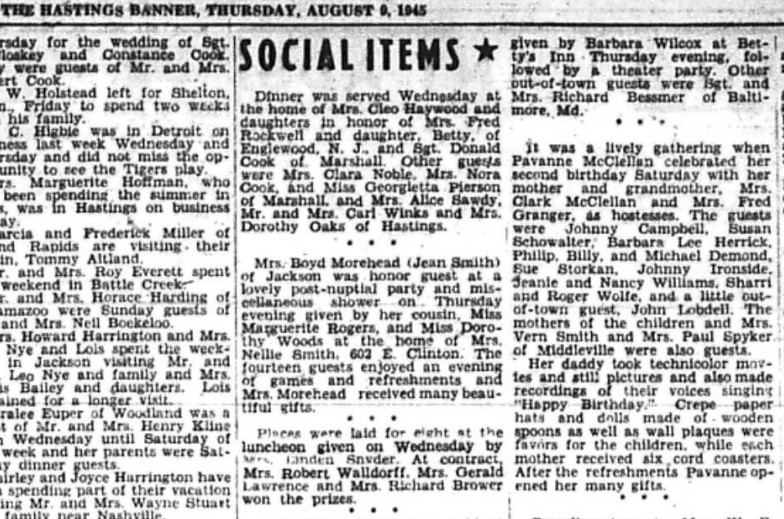

In the August 9, 1945 issue, in the right-hand column under “Social Items”, there was the record of a second birthday party for Kay’s older sister, Pavanne. (In future stories, Pavanne wishes to be known as Ada, Bell, Sophia, or Suzanna. Kay is mulling over these options, currently favoring Sophia or Bell, as both names appear among their ancestors. But anyway, the sisters will work this out together. For today and to avoid confusion, we’ll keep to the beautiful name of Pavanne.)

Kay scanned and sent the clipping to her sister who still resides in Michigan. Here is the reply she received by text:

“The Hastings birthday party made me smile. I loved that you found it and shared with me. I felt special and loved. I actually had a first and last name! Funny I have my baby book and Mom taped over every place it said Pavanne McClellan. She taped the McClellan so you couldn’t see any of them. I will think a good thought that in her way she was trying to protect me or herself. It’s okay.”

Kay worries a little when she sends such fragments to her sister. She knows that years of pain, confusion, and loss went into the ‘good thought’ her sister is now able to muster. She knows that even to thank her kid sister for finding such a clipping, the big sister must set aside difficult memories.

Families have secrets. In this family, Kay – for good or ill – was nearly always the detective and breaker of silences. But the first breaker was Pavanne herself. She waited her whole childhood to speak; she waited Kay’s whole childhood.

In the early 1980s, when Kay was living in London, working for a feminist campaign group, dying her Jean Seberg haircut haircuts green and pink, and going to gigs at the Rainbow Theatre, she received an important visit from Pavanne. One afternoon during that London visit, the sisters strolled across Hampstead Heath, ending up at the Holly Bush pub.

Here is the room where they drank wine and shared bar snacks:

Of course, the Holly Bush was not empty as in this photo, and by evening, the pub grew crowded with customers lining the bar for orders, then standing and sitting throughout the space. A busy pub is a human swarm, it heats the room, sucks the air from the room, then breathes it back smelling of beer, wine, and hard stuff in a hum of human voices. The whole thing – this hum and body heat and swarm-ness – presses the walls and windows and doors of the pub before breaking out into the street where, these days, the smokers congregate. Nobody in the pub, of an evening, can know all of what it holds: stories, memories, rumors, plans made, secrets divulged, political debates, and lovers’ promises and betrayals. The sisters, pressed further into a corner of the room as the evening wore on, knew only their small share.

“The evening wore on…That’s a very nice expression, isn’t it? With your permission, I’ll say it again,” Kay says.

I laugh. “You and your love of cliché.1 Go on, then, say it again if you like. But I don’t promise I will add it to the story.”

“It’s a line from a film, stupid!” she says. “It slipped from my mouth without my conscious volition. It’s just there, in my body along with every other hackneyed line in the world, waiting for its moment.”

So, Kay insists we pause to remember an old Jimmy Stewart film, the one about his friendship with a tall rabbit named Harvey. This, Kay says, is because of two highly relevant lines in the film. The first occurs in the bar scene from which Kay has pilfered her clichéd phrase: the evening wore on. In the scene, Elwood P. Dowd (Stewart) describes the first meeting between his leporine friend, Harvey, and the psychiatrist who plans to commit the apparently delusional Dowd to hospital:

“At first, Dr. Chumley seemed a little frightened of Harvey, but that gave way to admiration as the evening wore on. (sigh) The evening wore on…That’s a very nice expression, isn’t it? With your permission, I’ll say it again. The evening wore on.”

“And with your permission, I’m gonna knock your brains out,” returns the bullish psychiatrist’s fixer who wants to throw Dowd back onto the locked ward where few patients are heard from again.

The second line, gently delivered by Stewart: “Nobody ever brings anything small into a bar.” Words to fit perfectly the conversation that would unfold between the two sisters that night.

Okay, we’ve got that out of the way. So, as the evening wore on there in the Holly Bush pub, nearly two centuries after the pub was built, decades after the old Hollywood movie that now nestles in Kay’s memory waiting for its moment, and where Pavanne and Kay sipped wine and reminisced, it slowly emerged that Pavanne had something big to tell Kay. “Because nobody ever brings anything small into a bar,” Kay elbows me.

“Cheesy redundancy really is your middle name, Kay,” I tease.

Kay shrugs as if to say, can’t be helped! Then, as if her thoughts had taken a turn, her face darkens with concentration. Kays tells me that as the sisters sipped wine and talked about growing up with an eleven-year age gap between them, Pavanne was working up to a disclosure.

It came in the middle of a spell of laughter over shared memories. Pavanne laying out prom dress patterns on their bedroom floor, Kay stepping on them and yelping about the straight pins. Hiding her sister’s Elvis records after a quarrel. Pavanne babysitting, having to take her kid sister along to Saturday matinees at the old Shafer Cinema on Ford Road. They saw sci-fi movies, the ‘pods and blob’ films of the fifties, and James Dean teenage delinquent stories, but mostly they went for the Elvis movies. Pavanne was crazy about Elvis in those days. Yet halfway through the film, Kay knew her sister’s seat would be empty. She would make her way up the dark aisle, groping the backs of seats to her left and right to steer herself forward. She knew Pavanne would be in the ‘john’ as she called it, smoking cigarettes and ratting her hair with a bunch of other girls.

The sisters laughed hard, perhaps a little too hard at these fragments, the annoyance of a kid sister when you are trying to be a cool teenager, because then, as sometimes happens to us all, Pavanne’s laughter flipped to tears. Heavy tears. Prolonged, grief-stricken, dam-bursting sobs. There in the corner of the Holly Bush, drawing a few stares from the next table.

“I’m not your sister,” she said finally, choking on the words and expelling a distressing thought that must have tormented her as she grew close to the revelation. She said it again, as if demanding that Kay agree.

It’s a human tactic and a self-protective one: begin with the worst interpretation of a fact or situation. Walk deep into the shadows before looking for light.

“What?”

“I have a different father.” A first step away from the worst, because the first line must be followed by a second line, and we humans are a hopeful lot.

It was the night nearly thirty years of Kay’s innocence about family crashed to an end, though as often happens when familial silences are broken, the release of this particular secret would both shock and not shock. We often realize that we have ‘known all along’ – perhaps not the thing itself, but that there was a thing.

Pavanne told Kay her secret that night, what she knew of her own past, what she did not know. She told Kay how, without it ever being said explicitly, she had grown up understanding that she must never speak of it. When she flew home the next day, she informed their parents that she had spoken, that Kay knew, and she asked that her parents tell Charlie, her brother, as early as possible. When they failed to do so after many months, Kay flew to America and told him. This lit some fires beneath family gatherings for a few years. And it set in motion Pavanne’s further searches for her father and her story.

For the sisters and brother, the new information altered the way they remembered particular incidents in childhood. Nearly every family celebration or passage or difficulty took on a new aspect. As Kay has said elsewhere, the light fell differently on their memories. Charlie and Kay must consider that they had not seen the painful isolation of a person growing up as close as anyone can be. All three saw that the parents – two fathers and a mother – had grown more, not less, mysterious. There was an initial anger that would find, in the years to come, its way back to forgiveness and love, but this time without forgetting the injured person in the midst.

As for Pavanne, a sister true who shall be named Bell or Sophia as she wishes in the stories to come, she’s living proof that one is not born a sister, but becomes one. Sisterhood and brotherhood are not given, not necessarily biological, they are something we make.

Something else we have ‘known all along.’

The evening wore on:

Big things in the bar:

Leave a comment