“You don’t like your Dad much, do you Kay?” Audra spoke this line as though it were a light-hearted tease or private family joke, but I heard a tinge of resentment in her voice and in the remark itself. Why else would the remark have stayed with me for more than half a century? There was a mysterious grievance emanating from my mother and clouding the atmosphere inside the car. I guess now I might call her remark a barb, but as a child, I would not have found that word. And I wonder if the barb was directed at me, at Jake for encouraging me, or both of us. I doubt Audra fully knew the answer to that question, although the barb was hers. But I am certain that it was a barb, though probably not one that brought Audra any joy or satisfaction.

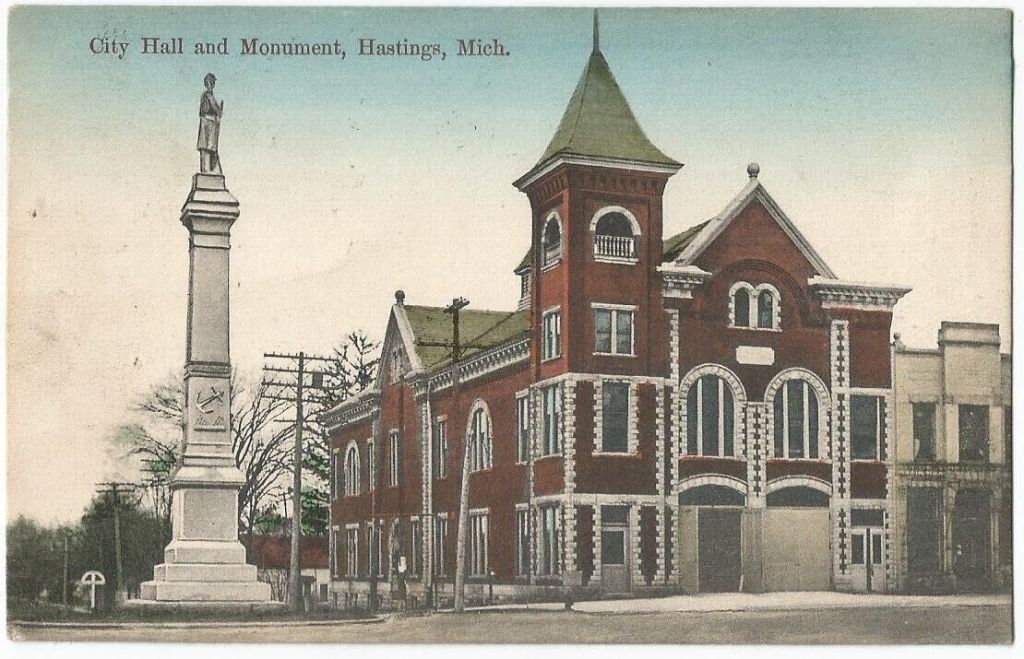

It was the summer of 1960 and we were on our way to the annual family reunion and picnic in Hastings, Jake’s hometown. It’s a good two-hour drive from the suburbs of Detroit to the western side of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula. In those days before seatbelts (and in between reprimands from the parental front seat), my brother Charlie and I were unruly in the back seat. We rolled around, played, teased one another, argued, hung our heads out the windows, and waved at the other drivers and passengers. But most of all, I liked to grab the spot right behind my father. I liked to wrap my arms around Jake’s neck while he drove. I liked to anticipate our arrival in Hastings where Jake would point out his statue right next to the city hall, and I would ooh-and-aah and celebrate the importance of my father to his hometown.

It would be a few years before I realized that this was a statue not of Jake but of a Union soldier commemorating the town’s losses during the Civil War. I didn’t mind that a trick had been played on a gullible child. I didn’t mind hearing the adults laugh about it when Jake’s ruse was revealed at one of the reunion picnics. As a little girl, I loved every moment of believing that was Jake up there. And although the statue of Jake has long since gone the way of God and Santa Claus, and I am now sensibly adult about tall tales, I still recall the feel of believing and the stomach butterflies taking flight at each arrival in Hastings and the vision of Jake high above the town.

I can still see myself on the day of Audra’s remark. I am hanging on Jake’s neck and kissing it and talking about the statue. He doesn’t seem to mind. Then Audra said what she said and I felt scolded without having the words for it. I shrank back into the rear seat and pretended not to care. That is something you do when words don’t come. I elbowed Charlie and he elbowed me and I went back to being an annoying kid sister in the back of the car.

But now, I think about the hero-making that goes on in families, in our case a pact between father and daughter. I see the deceptions and wounds alongside its sweetness. I see the tiny, shifting, and poorly understood alliances and fault lines in family groups. How deeply ingrained they are in who we become, so much so that we may forever lament all life that follows childhood. Later, we may sense that life never lived up to some richness and promise in childhood that we still cannot quite name. We may come to believe that nobody wants to grow up, not really.

So the light falls upon this memory differently each time I return to it. It falls differently upon our westward Ford making for Hastings, the highway, the front seat and back seat, my brother and me, our parents, and my sister who was not there that day. It falls differently on that old statue in town and the heroic young car salesman who was my father. And finally, it falls differently on Audra who, I now think, must have been enduring some injury to her motherhood caused by the frequent preference her youngest child showed for her father. Yes, perhaps all this puts Audra’s remark in a different light too.

Leave a comment